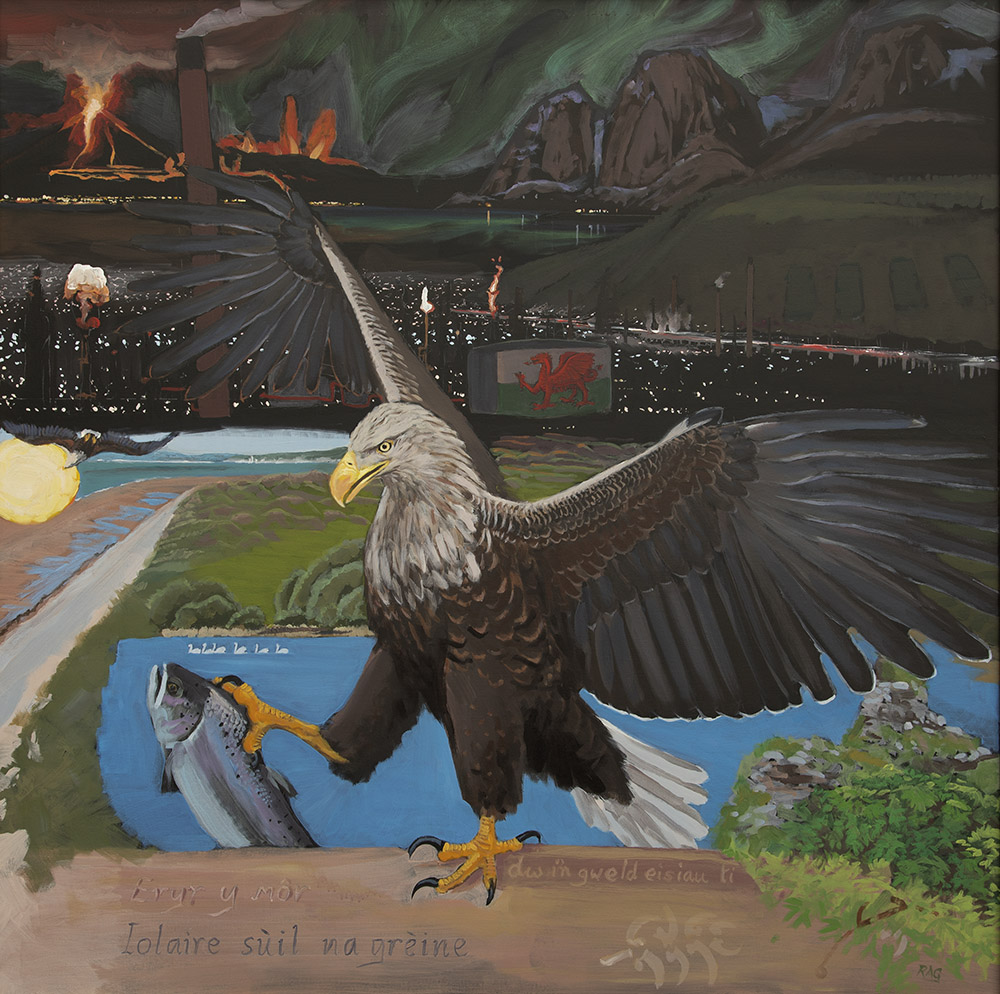

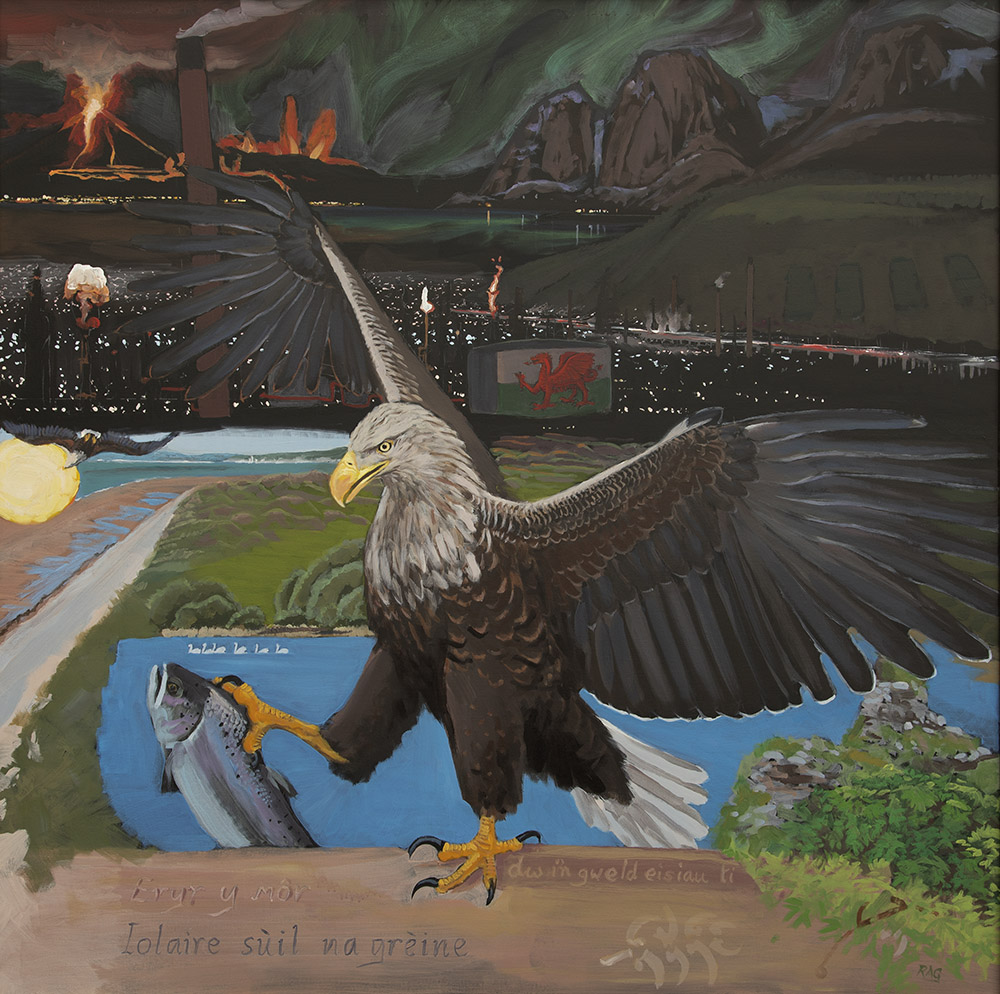

I wanted the eagle to be life size. The White-tailed Sea Eagle is a huge eagle, often referred to as flying barn doors.

This worries some people, why would we want an eagle that big back in our landscape, wont it carry off lambs, or worse. In Norway there are several thousand pairs of White-tailed Sea Eagles living alongside livestock farming and there has never been a single proven incident of these birds taking healthy sheep lambs.

I wanted the painting to be about Wales and to raise funds and awareness for the Eagle Reintroduction Wales project which is gathering pace. Growing up in Wales I had no idea then what I was missing as we drove along the ‘Mary Poppins road’ as we liked to call it over the rooftops of Port Talbot, past towering chimneys of the refinery and beneath steep sided forested hills.

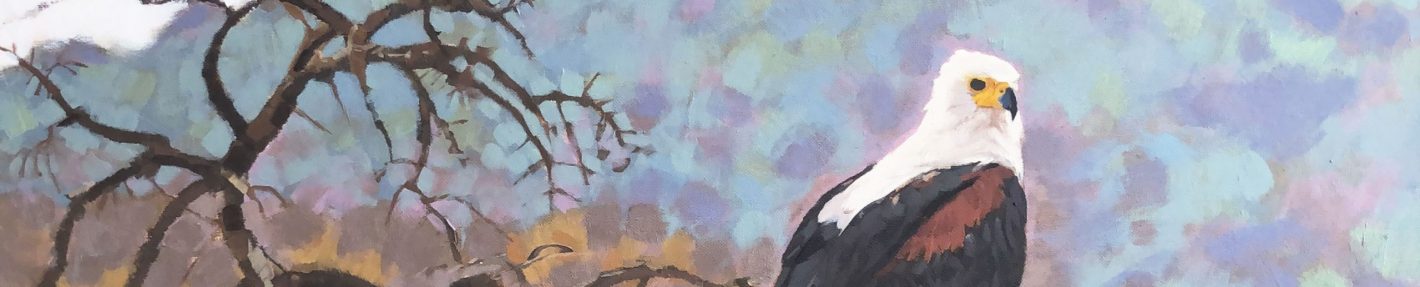

Coming back, after a life time of watching and studying eagles in Africa I felt the absence of these birds from our Welsh landscapes.

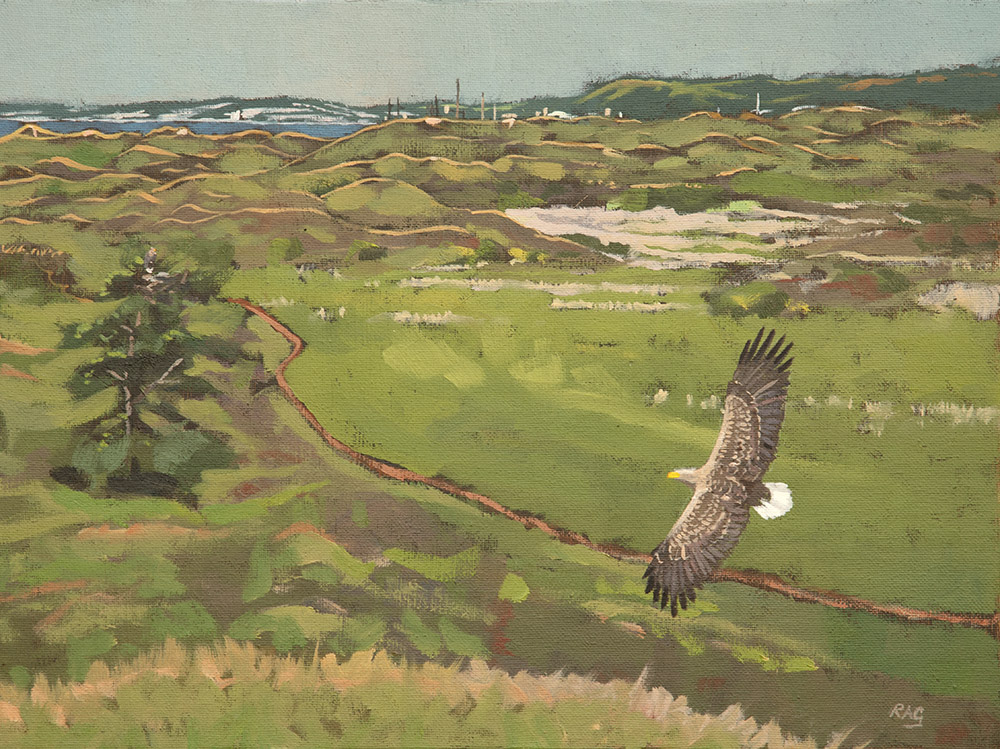

On Kenfig Burrows, a sand dune system close to Port Talbot, the last White-tailed Sea Eagles were recorded in Wales. The year was 1816 and we have a good record because William Weston Young, who ran a pottery factory nearby, made a watercolour painting of the event. It shows the female eagle of the pair held in a gin trap with a fox watching on from nearby, and the mate of the eagle flying overhead. In his notes he describes how the mate stayed close by for 24 hours until the female was removed from the trap and killed. Despite efforts they never managed to catch the male and we wonder what became of him after he left the area.

There is a wonderful book by William Horwood (who wrote the famed mole equivalent of Watership Down: Duncton Wood) called the Stonor Eagles which I read in 1984. I read the book again at the start of this painting to remember it all and it is a major inspiration for this painting. It is a beautiful blend of mythology describing the origin of the first Sea Eagle from the battle between land and sea in Iceland, a concurrent story following the life of the last Sea Eagle driven out from the UK, and the life and career of a sculptor who carves great statues of the birds on the cliffs in Norway.

The disappearance of Sea Eagles from the UK corresponds to the industrialisation of Britain especially from the South Wales Valleys where coal and iron ore offered the home for the evolution of guns and shooting, railway lines and steam engines and eventually steel refining. Activities of gamekeepers since the late 1800s have caused a major upset to the ecological processes in Britains upland areas which were first manifest in irruptions of rodents, cycles and eventually parasites and diseases which normally a healthy population of predators would remove. Thankfully we are at last seeing a move to nature restoration including the bringing back of missing species.

Before all the shooting and game estates there was a time in Britain when Sea Eagles were revered and occupied spiritual significance to people. Three thousand years ago the cultural capital of Britain was on Orkney and a burial chamber has been discovered there where people were buried alongside many remains of sea eagles. The arrangement of talon remains in other parts are thought to represent neanderthal jewellery. The Gaelic name for White-tailed Sea Eagle, ‘Iolaire sùil na grèine’ means bird with the sunlit eye.

More recently, but the oldest Welsh prose story (from 1350, contained in the Mabinogion) documents how eagles and salmon are celebrated to be the most ancient and wisest living creatures. Arthur sends Gwrhyw the Interpreter of Languages along with Culhwch to go and find a hero called Mabon son of Modron. As with Horwood’s book, Gwrhyw can speak the languages of animals and birds. So they decide to ask the oldest animals for help. The eagle tells of how when he came to this place he perched on a rock from which he could peck at the stars but he had been there so long that now he could not reach them. The story recounts a struggle between the eagle and a large salmon along the Severn Estuary towards Gloucester. The struggle ends with friendship and optimism as the salmon helps them find Mabon.

Seeing a Sea Eagle on a large salmon is far from the imagination in South Wales now but in mediaeval times it would have been quite usual for people to encounter this especially as they lived then so close to nature. Even today, there a frequent posts on social media of Bald Eagles and African Fish Eagles with their talons locked into a large fish and unable to get airborne. Unlike Ospreys these eagles do not enter the water but snatch fish and prey from the surface but sometimes they cannot gauge the size of the fish they are attacking. White-tailed Sea Eagles and salmon also feature in Icelandic folklore where it is considered exceptionally bad luck not to help an eagle struggling with a huge fish in the water.

Port Talbot is the most amazing place and I was inspired to show the steel works at night from the film Bladerunner with Harrison Ford who is a fantastic supporter of conservation through his work with Conservation International. It is a bit of an apocalyptic scene but the industries there and in the Valleys have been such an extraordinary formative achievement for Wales & Britain and the communities have formed many of our great Welsh artists. So I wanted the dragon to be in the painting! The Mabinogion also contains accounts of the origin of the red dragon as our emblem for King Arthur, Owain Glendwr and for Wales. The red dragon represented the fight of the Britons against the Anglo-Saxon white dragon and the ‘second plague’ was the screaming fight between these two dragons which continues beneath a castle in Snowdonia!

The other point is that wild emblematic creatures like the Sea Eagle can actually exist completely within some of our most built-up and human-transformed habitats. I saw the species doing really well in Germany, while in North America, Ospreys and Bald Eagles nest within precincts of major cities with waterways. And I wanted to present this slightly surreal view of a very wild creature within a human industrial scene.

The painting portrays the evening of the industrial age that we are now experiencing and a look towards perhaps a more optimistic healthy cleaner environmental future for the people of Port Talbot and South Wales with new opportunities for energy, conservation and tourism. I have included in the painting some of the key landmarks and as much of the ‘sense of place’ as I could from the amazing habitat around Kenfig Nature reserve looking towards Swansea Bay.

Norway features prominently in the story of Cuillen by William Horwood and has been crucial as the source of birds to restock Scotland through the RSPB work of John Love, Roy Dennis and Dave Sexton, and to Ireland through the work of the Golden Eagle Trust and Allan Mee. I was lucky to meet Allan in Ireland and he showed me how well the eagles are doing there. Laurie and I made the journey to Lough Dough to see the first young eagle in over 100 years. Torgeir Nygård has helped with the supply of these birds from Norway and I met Torgeir in Trondheim where I attended a raptor conference. He showed me the amazing situation of some 60 pairs of Sea Eagles coping with some 60 wind turbines on the island of Smola. Some mortalities every year but the population manages to persist there. I took him a bottle of Penderyn whiskey which was very much appreciated as we gazed at some amazing northern lights in the Scandinavian sky! so they had to be in the painting.

The success of any of these projects is entirely dependent on having the right people involved. Sophie Lee Williams from Eagle Reintroduction Wales and my great friend Carl Jones from The Durrell Trust together with their respective teams are indeed the right people for Wales and they are doing a fantastic job paving the way for these birds to come back, possibly somewhere along the Severn Estuary not far from the site of Wales’ oldest Welsh prose story of the eagle and the salmon.

Three smaller oils that were done en plein air on site at Kenfig NR, also on show at the exhibition…